On Jan. 3, 1968, a surface-to-air missile shot down U.S. Navy Capt. Edward Dale Estes’ A-4 Skyhawk aircraft over North Vietnam. Estes ejected from his damaged aircraft and landed safely, only to spend 1,898 days—more than five years—as a prisoner of war. For the first two years of his imprisonment, his wife and two young sons did not even know his fate.

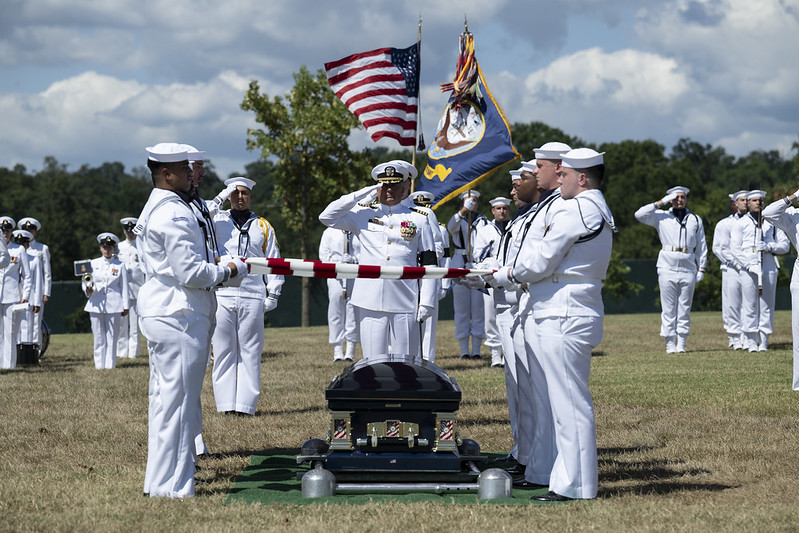

On Aug. 25, 2025, Estes’ family came to Arlington National Cemetery to say goodbye to the decorated pilot, husband, father and grandfather during a service that included full military funeral honors with escort. Estes’ wife, Bette, wore her husband’s gold aviator wings; their sons, Ed and David, wore POW/MIA lapel pins.

When Bette received the folded flag that the honor guard had held over her husband’s casket, she thought of his faith in his country and fellow service members. “He loved the Navy,” she later said. At the end of the service, Bette placed a rose on her husband’s casket as her sons, on either side of her, put their arms around her. They then reflected on his life and growing up with a missing father during wartime.

Bette recalled that the first two years, when Estes was listed as missing in action, were hardest. “You just vacillate, you just think, ‘is he there, or is he not?’” she said. “But then you just have to go on with your life and your routine.”

At the time, the family lived at Naval Air Station Lemoore, California. Ed was seven years old, and David was five, when their father went missing. They lived among other children whose fathers were either imprisoned, missing or killed in action. “They were all pilots’ kids,” Ed recalled. “The Navy took good care of us.”

One day in 1970, Ed came home from elementary school and found a letter from his father in the mail. “The North Vietnamese must have let it slip through,” he said. He brought the letter to his mother and, the next thing he knew, Navy cars were pulling up in front of the house. The letter officially changed Estes’ status from MIA to POW. “Just knowing that he was still with us was a really good feeling,” Ed recalled.

After five long years of imprisonment in jungle camps and the infamous “Hanoi Hilton,” Estes finally returned home with other American POWs on March 14, 1973, as part of Operation Homecoming. The family vividly remembered traveling to Travis Air Force Base, California, to greet him. Ed and David were now 12 and 10 years old. David recalled waiting on the tarmac as other POWs came down the aircraft’s boarding stairs and saluted the awaiting officers as their families ran to them. At last, Estes appeared in a khaki Navy uniform. Bette noticed that he looked thinner but did not seem to have aged. Ed thought his father “looked like he just stepped home. It was just a happy day.”

When the POWs were brought home, they stopped at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. Estes told Bette that he “took a shower for an hour, because in the camps they would throw a bucket of cold water over their bodies, and that would be a shower.” She also remembered his first meal request: bacon and scrambled eggs.

According to Ed, Estes did not talk about his POW experiences until the last ten years of his life. “He didn’t get into a lot of detail, but he told us about the ‘tap code’ [used to communicate with other POWs], and how they would put messages on the bottom of their tin cups and their bathroom buckets.”

Estes’ Silver Star citation describes the harsh conditions he overcame: “His captors, completely ignoring international agreements, subjected him to extreme mental and physical cruelties in an attempt to obtain military information and false confessions for propaganda purposes. Through his resistance to those brutalities, he contributed significantly toward the eventual abandonment of harsh treatment by the North Vietnamese, which was attracting international attention.”

Despite his five years as a POW, Estes wanted to remain in the Navy. “I wasn’t totally shocked,” Bette said. “Ever since he was young, he wanted to fly.” She did not try to talk him out of it. “I love Navy life,” she added.

Estes served for more than 30 years, beginning with his enrollment in the Navy’s Aviation Cadet program in 1955. Prior to his Vietnam service, his assignments included flying in defense of Guantanamo Bay during the Cuban Missile Crisis in the fall of 1962. Estes retired in 1986 at the rank of captain.

Toward the end of his life, Estes told Ed to decide where he would be buried. The family decided on Arlington National Cemetery. “It's such an honor to be here amongst all those heroes, those that sacrificed and all that history,” Ed concluded. “He deserved this honor.”