On Feb. 10, 1968, a C-130 Hercules transport aircraft braved intense enemy fire as it approached the landing strip at the besieged U.S. Marine Combat Base at Khe Sanh in South Vietnam. As it prepared to touch down, enemy bullets riddled the cockpit and fuselage.

Marine Corps Cpl. Robert Scruggs would later tell his three children about the chaos of that day. On the ground, Scruggs watched flames erupt from the craft and saw it careen off the runway, spin and come to a stop. The sight of the crash remained with him for the rest of his life. Scruggs also told his children that he had been shot in the leg while patrolling outside Khe Sanh’s perimeter and showed them his scar. “It was hard to get the full story from him,” Amy Scruggs said. “You got pieces of stories over the years and then you had to squish them all together.”

Marine Corps Cpl. Robert Scruggs would later tell his three children about the chaos of that day. On the ground, Scruggs watched flames erupt from the craft and saw it careen off the runway, spin and come to a stop. The sight of the crash remained with him for the rest of his life. Scruggs also told his children that he had been shot in the leg while patrolling outside Khe Sanh’s perimeter and showed them his scar. “It was hard to get the full story from him,” Amy Scruggs said. “You got pieces of stories over the years and then you had to squish them all together.”

On July 24, 2025, Robert Scruggs II, Kimberly Bradigan and Amy Scruggs came to Arlington National Cemetery to reminisce and honor their father's service in Vietnam—including during the siege of Khe Sanh, a seminal moment of the war.

During the 77-day siege, from Jan. 21 to Apr. 6, 1968, Scruggs, his fellow Marines and their South Vietnamese allies lived in underground bunkers. They withstood artillery, mortar and rocket attacks; aircraft flying into the base perimeter often came under fire. When Scruggs finally made it off the base, his best friend took his bunk in one of the bunkers. Twelve hours later, the North Vietnamese attacked and his friend was killed in an explosion. “If our father would have been in his bunk,” Robert said, “he would have been dead.”

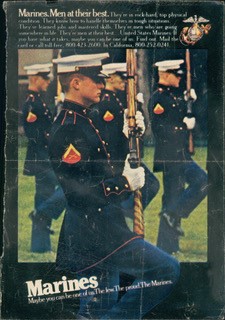

After returning from Vietnam, Scruggs joined the Marine Corps Silent Drill Team. He performed all over the country—even on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” where he met singer Nancy Sinatra. While serving with the Drill Team, Scruggs noticed a Marine recruiting ad in a magazine that featured him wearing his dress blue uniform. He immediately recognized the “Tiger stripes,” or wood grain, on the rifle’s stock. “He said, ‘that’s how I knew it was me,’” Robert recalled. “It was a surprise to him.”

In his later years, Scruggs told his children that he wanted a military funeral. “He was so proud to be a Marine,” Kimberly said. “We thought, what better way than to do it than at Arlington National Cemetery.”

At the funeral service, U.S. Navy Chaplain (Lt. Cmdr.) Doyl McMurry told Scruggs’ family and friends that he “exemplified the Marine Corps’ core values of honor, courage and commitment.” When Robert received his father’s flag from Marine Corps Staff Sgt. Randy Harshbarger, he thought of his father and how much would have enjoyed the service: “This is exactly what he would have wanted,” he reflected.