The first Jewish woman appointed to the Supreme Court, and the second female justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg served on the nation’s highest court from August 10, 1993 until her death from metastatic pancreatic cancer on September 18, 2020. Described by Chief Justice John Roberts as “a tireless and resolute champion of justice,” Ginsburg steadfastly advocated for the equal rights of all U.S. citizens regardless of gender, race or religion. Soft-spoken and small in stature, Ginsburg may have seemed “an “unlikely revolutionary” (as the Washington Post’s obituary described her), yet her vision of justice transformed not only the law but also the cultural landscape. “The Notorious RBG” — as supporters affectionately dubbed her — became a veritable icon who inspired multiple generations.She is buried in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery, alongside her husband, Martin Ginsburg, an attorney and U.S. Army veteran.

Early Life and Education

Ruth Bader was born in Brooklyn, New York, to working-class Jewish parents. Her father, a furrier, had immigrated from Russia as a child; her mother, the daughter of Polish immigrants, also worked in the garment industry. Bader’s mother — who died the day before her high school graduation — had not been able to attend college, and she inspired Bader to pursue education as a means of independence and empowerment. The family’s Jewish identity, as Justice Ginsburg later said, also informed her career: “The demand for justice runs through the entirety of the Jewish tradition,” she stated in 1996.

Ginsburg attended Cornell University on a scholarship, graduating in 1954 at the top of her class. That same year, she married fellow Cornell graduate and ROTC Army officer Martin Ginsburg — “the only young man I dated who cared that I had a brain,” she quipped. Martin Ginsburg, known to friends and family as Marty, would become a prominent tax attorney and law professor. The couple’s romantic and intellectual partnership lasted 56 years, until his death from cancer in 2010. They had two children, Jane and James.

In 1955, Ginsburg began law school at Harvard University, where her husband Marty had also enrolled following his two-year Army service. One of only nine women in a 552-person class, she endured gender discrimination — women could not use certain sections of the law library, for example — but nonetheless became the first woman selected for the Harvard Law Review, one of the nation’s most prestigious legal journals. Ginsburg gave birth to her daughter Jane in 1955, the same year that Martin Ginsburg was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Yet even as she devoted significant time to caring for her baby and husband, she continued to excel academically. As Ginsburg recalled in the award-winning 2018 documentary “RBG,” she spent time with her family after returning from her classes, and then, after the baby went to sleep, worked late into the night on her studies — a pattern that would continue throughout her career. After Martin accepted a job in New York, she transferred to Columbia Law School and graduated at the top of her class in 1959.

Pre-Supreme Court Career

Despite such sterling credentials, Ginsburg faced significant professional barriers in her early career. “In the Fifties,” she later recalled, “the traditional law firms were just beginning to turn around on hiring Jews. But to be a woman, a Jew and a mother to boot — that combination was a bit too much.” Although a professor had recommended Ginsburg for a clerkship with Justice Felix Frankfurter, he declined even to interview her, and she received no offers from law firms in New York. This pattern of discrimination recalled previous experiences: in 1954, while Martin was serving at an Army base in Oklahoma, a job offer from the local Social Security office was withdrawn when Ginsburg disclosed that she was pregnant.

Ginsburg found greater opportunities as a law professor, teaching first at Rutgers University (1963-1972) and then at Columbia (1972-1980), where she became the first female law professor to earn tenure. While at Columbia, she worked in Sweden on an international civil law project, and Swedish feminism influenced her thinking on gender equality and the law.

In 1972, Ginsburg stepped onto the national stage when she co-founded and served as the first director of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). In this capacity, she argued six cases before the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1978, winning five. She became known for her careful yet pointed oral arguments, which explained how the law created and sustained gender inequality — with negative consequences for both women and men. Indeed, one of her most significant cases, Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld (1975), effectively ended gender-based distinctions in Social Security spousal benefits, allowing men to receive survivors’ benefits previously granted only to widows. In recognition of her success in such landmark cases, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1980.

Supreme Court

When President Bill Clinton announced Judge Ginsburg’s nomination to the Supreme Court on June 15, 1993, he described her as a consensus candidate, neither liberal nor conservative. “She has proved herself too thoughtful for such labels,” Clinton said. After a 96-3 Senate confirmation, she took her seat on August 10, 1993. As an associate justice, Ginsburg continued to pursue what she described as a “measured” approach to judicial change, yet her decisions often had far-reaching implications. In 1996, for example, she wrote the majority opinion in United States v. Virginia, a landmark gender equity case which held that Virginia Military Institute’s all-male admissions policy was unconstitutional.

When President Bill Clinton announced Judge Ginsburg’s nomination to the Supreme Court on June 15, 1993, he described her as a consensus candidate, neither liberal nor conservative. “She has proved herself too thoughtful for such labels,” Clinton said. After a 96-3 Senate confirmation, she took her seat on August 10, 1993. As an associate justice, Ginsburg continued to pursue what she described as a “measured” approach to judicial change, yet her decisions often had far-reaching implications. In 1996, for example, she wrote the majority opinion in United States v. Virginia, a landmark gender equity case which held that Virginia Military Institute’s all-male admissions policy was unconstitutional.

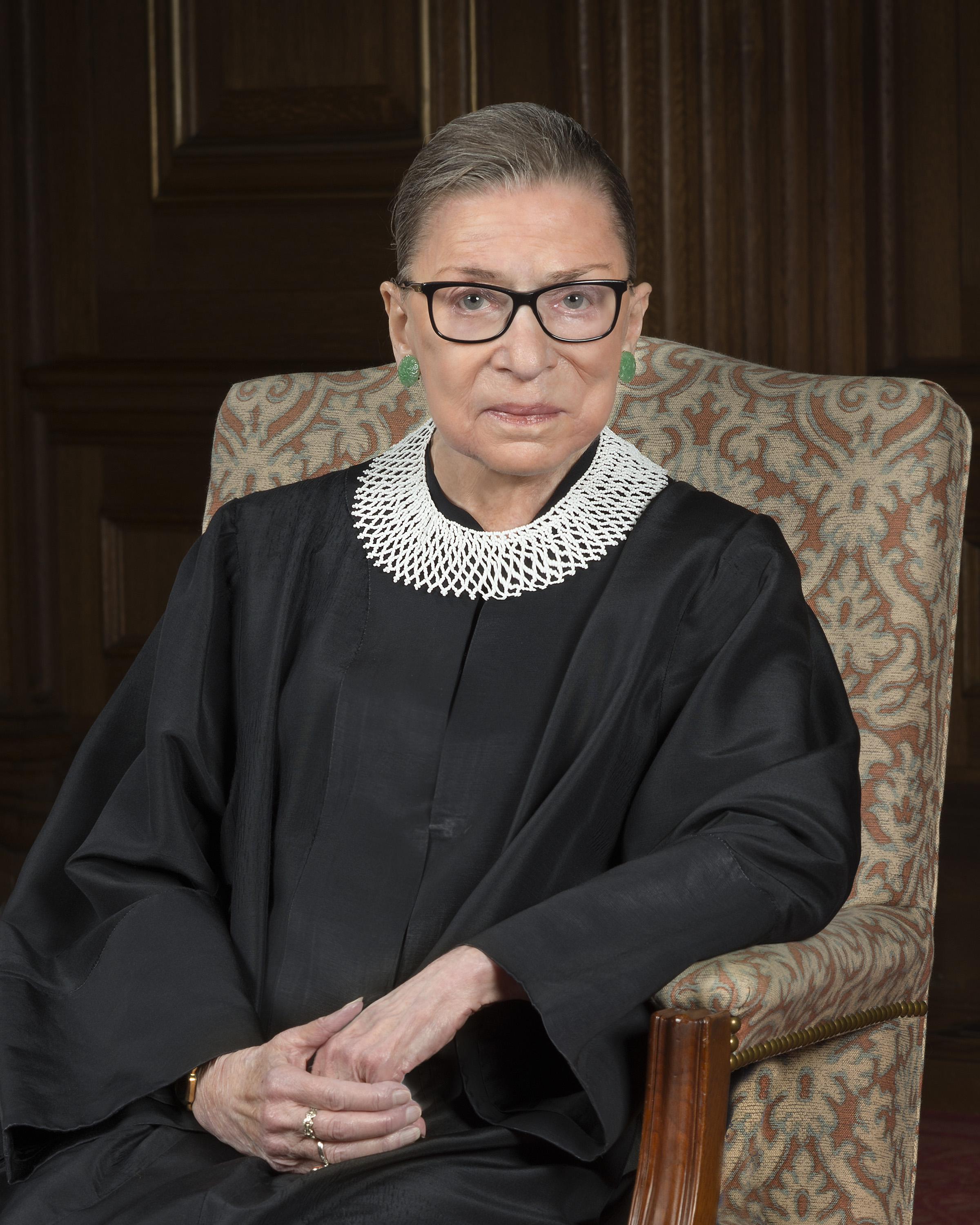

As the Supreme Court became increasingly conservative in the 2000s, Ginsburg began to be known for her forceful dissenting opinions, often articulated in oral arguments. With the retirement of Justice John Paul Stevens in 2010, she became the Court’s senior liberal justice and an increasingly public symbol of resistance to its rightward turn. The style-savvy justice famously donned her “dissent collar” — a spiky, metallic twist on the signature lace collars that she wore above her robe — when, in the words of a New York Times fashion critic, she “read her equally spiky dissents from the bench.”

Leading the Court’s four-member liberal minority, Ginsburg issued prominent dissenting opinions in cases on gender equality, voting rights and religious freedom, among other key issues. In Lilly Ledbetter v. The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., Inc. (2007), she read an impassioned oral dissent defending women’s right to equal pay; although the Court’s majority ruled against Ledbetter’s gender discrimination suit, two years later, President Barack Obama signed into law the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Restoration Act, which reflected the principles of Ginsburg’s dissent. In Shelby County, Ala. v. Holder (2013), she argued that the majority ruling to dismantle key provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act was “like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” And in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014), her dissent maintained that private corporations could not use religious freedom laws to deny health care coverage to employees.

Death and Legacy

In the last two decades of her life, Justice Ginsburg battled colon cancer and pancreatic cancer, yet she did not miss a day of oral arguments until the Supreme Court’s 2018 term — even after surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, and the death of Marty Ginsburg in 2010. Although many worried that she looked frail, the “Notorious RBG” became famous for her strength training regime. (In the documentary “RBG,” she works out with her trainer while wearing a sweatshirt that reads, “Super Diva!”)

In the last two decades of her life, Justice Ginsburg battled colon cancer and pancreatic cancer, yet she did not miss a day of oral arguments until the Supreme Court’s 2018 term — even after surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, and the death of Marty Ginsburg in 2010. Although many worried that she looked frail, the “Notorious RBG” became famous for her strength training regime. (In the documentary “RBG,” she works out with her trainer while wearing a sweatshirt that reads, “Super Diva!”)

On September 18, 2020, Justice Ginsburg died at her home from complications of metastatic pancreatic cancer. She was 87 years old. Her death on Rosh Hashanah, one of the holiest days in Judaism, signified to many Jewish observers that she was a “tzadik,” or righteous person; Justice Stephen Breyer stated that he had learned of her death while reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish. On the day before her death, the National Constitution Center had awarded Ginsburg the 2020 Liberty Medal for her “efforts to advance liberty and equality for all.”

Prior to her private burial ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, Justice Ginsburg lay in repose at the U.S. Supreme Court building for two days. On September 23 and 24, 2020, long lines of mourners waited to pay their respects to her. Then, on September 25, her flag-draped casket lay in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Ginsburg was the first woman in American history to receive this honor.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s remarkable life and legacy is perhaps best summarized in her own words, as she expressed when receiving Harvard’s Radcliffe Medal in 2015: “Fight for the things you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.” She may now be joined by all who honor and remember her at Arlington National Cemetery.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is buried in Section 5, Grave 7016-1.

Photo Credits

- U.S. Army photo by Elizabeth Fraser/Arlington National Cemetery. (February 16, 2022)

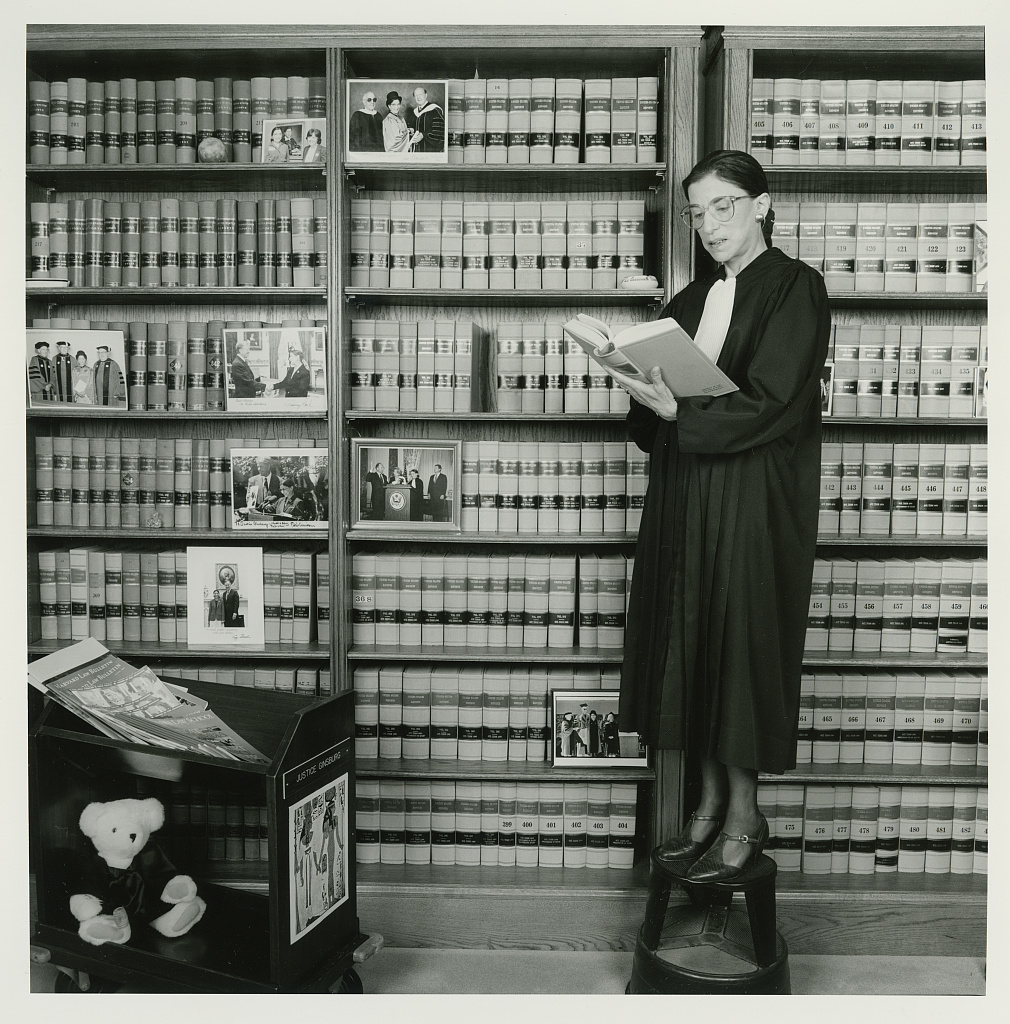

- Photo by Nancy Lee Katz, Library of Congress. (July 22, 1994)

- Official portrait, Supreme Court of the United States. (2016)

- U.S. Army photo by Elizabeth Fraser/Arlington National Cemetery. (February 16, 2022)