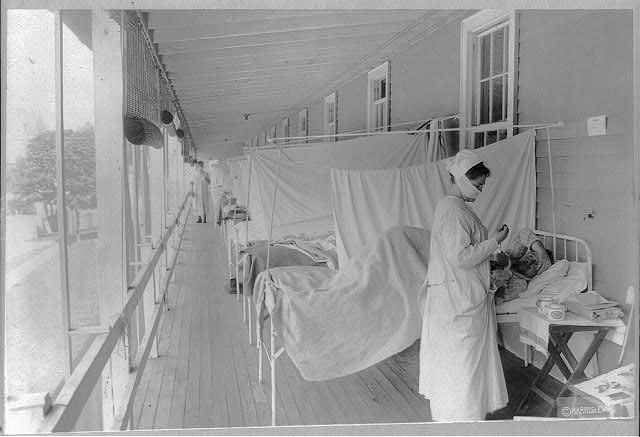

A nurse takes a patient’s pulse in the influenza ward at the Army’s Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington D.C., November 1, 1918. (Library of Congress)

As our nation and the world face the COVID-19 pandemic, ANC’s team of historians has been looking back at another health crisis and reflecting upon how it impacted Arlington National Cemetery: the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. In particular, we have chosen to highlight the role of female military nurses during the influenza pandemic and how they are commemorated on Arlington’s memorial landscape. By sharing this story and paying tribute to these frontline health care workers from the past, we can honor the health care workers of today who are bravely fighting the current pandemic. Sharing this story is especially fitting during the annual celebration of the birthday of the U.S. Army, for Army nurses played a key role in the battle against influenza and paved the way for women to gain more opportunities to serve in the military.

The devastating outbreak of influenza that swept across the globe between 1918 and 1919 occurred during the final stages of World War I. With much of the world already reeling from the conflict, the combination of the war and the disease proved overwhelming and created a dual tragedy. Around 50 million people worldwide died from the influenza pandemic and about 500 million people contracted the disease, including civilians and members of the military. Although there remains no definitive explanation of where, when and how the influenza pandemic began, some scholars believe that the first known outbreak might have occurred at the U.S. Army’s Camp Funston in Kansas, or possibly, according to historian John M. Barry, in Haskell County, Kansas as residents came into contact with the camp.

Regardless of where it began, influenza exacted a dire toll on the American military, which had been involved in the world war since 1917. As service members crammed into camps, ships and trenches, the disease spread easily through the living conditions necessitated by war. Further exacerbating the situation, the mostly young service members formed one of the most at-risk populations for this disease: rather than being protected by their youth, people between the ages of 20 and 40 found themselves particularly susceptible to death in this pandemic. More than 55,000 U.S. service members are thought to have died as a result of influenza. Compared with the estimated figure of over 53,000 American battle deaths during World War I, the flu likely accounted for about half of all U.S. military fatalities during the war.

Who cared for these service men when they became ill? Female nurses. Tens of thousands of American women already served as nurses during the war, and they formed the front lines of the military’s battle against the influenza pandemic, just as nurses also did in civilian communities. Stationed overseas and in the United States, military nurses worked tirelessly to serve their nation alongside doctors, occupational and physical therapists, dieticians, and other specialists who supported the health of the American armed forces.

During World War I, American women served as military nurses through several avenues which had been established after the Spanish-American War, when women served as contract nurses with the military as well as in other volunteer groups. After leading the contract nursing effort during the Spanish-American War, Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee (Section 1, Grave 526B) played a key role in the creation of a permanent nursing service for the military. The lessons she and her colleagues learned in that conflict led to the establishment of the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and the Navy Corps in 1908, as well as the Army Nurse Corps Reserve. This reserve would function as a contingent of qualified nurses available for military service in addition to those already serving with the military. Under the leadership of Jane Delano (Section 21, Grave 6), the Red Cross Nursing Service became the official nursing reserve force of the military and supplied additional nurses for wartime service. While head of the Red Cross Nursing Service, Delano simultaneously served as the Army Nurse Corps’ superintendent from 1909 to 1912. Through these main organizations, thousands of women served as nurses during World War I. The Army Nurse Corps reached an estimated peak strength of over 21,000 by the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918.

Opportunities for women to serve as nurses, however, remained racially limited due to prejudice and the norms of segregation in the United States at the time. Eager to support the war effort, trained and qualified African American nurses wanted to serve as nurses but encountered many obstacles to their participation. In 1917, the American Red Cross reversed its previous policy of prohibiting African American nurses from enrollment, but took no immediate action to bring any African American nurses into the organization. After pressure from various African American leaders and organizations, the onset of the influenza pandemic eventually led, after the signing of the Armistice, to the enrollment of just 18 African American nurses in the Army Nurse Corps through the American Red Cross. These trailblazing 18 women became the first African American women to ever serve in the Army Nurse Corps.

Despite their essential roles with and within the military, especially during the influenza pandemic, female military nurses occupied a strange, undefined position. These skilled, professional women had no actual rank and did not receive benefits or pay equal to men. In the Army Nurse Corps, the women were neither officers nor non-commissioned officers; they had rank in name only, a confusing status which meant that their authority remained unclear. The 18 African American nurses received even fewer benefits than the white nurses, since they were not allowed to begin their service until after the Armistice. Nonetheless, all of these women put their lives on the line for their nation and their fellow Americans at home and abroad every day.

For nurses, the influenza pandemic became the most dangerous time of the war. During the outbreak, nurses cared for thousands of sickened soldiers. For the nurses in Europe, these ill men arrived in addition to the combat casualties from the battlefields. The situation proved dire as medical professionals could do little to help people stricken with influenza. Without a cure or effective treatment, nurses became even more important than doctors as they tried to decrease the suffering of their patients with their nursing care, blankets, food and kindness.

The nature of nursing work put these women at great risk to contract this highly contagious disease. Base hospitals overseas created specific infirmaries for ill nurses, and the American Red Cross set up two convalescent hospitals in France for service women. By October 1918, the influenza pandemic formed a major health crisis among the American nurses and medical staff overseas. While an exact figure for the number of American nurses who died during the war remains elusive, historians generally estimate it to be somewhere above 200. Most of these fatalities can be attributed to influenza, or complications from it such as pneumonia. While these women did not die on the battlefield and remained barred from full military service, they volunteered to serve the United States during wartime, and they gave their lives for their nation while fighting this disease.

At Arlington National Cemetery, the lives and service of these nurses are commemorated at the Nurses Memorial, located in Section 21. Once named the “Nurses Section,” this plot of land contains the graves of many military nurses from different time periods. Ongoing research by our team has revealed that the Nurses Section contains the grave of several nurses who likely fell victim to influenza during the global pandemic. While much research remains to be done on these nurses—and there may well be more stories yet to be discovered—we would like to share what we have found so far as a way to remember these women while we experience a pandemic in our own lifetime.

• Kathryn Mae Joyce (Section 21, Grave 47) served as a nurse with the Allegheny General Hospital Red Cross Unit from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, designated as Hospital Unit “L” under the supervision of the War Department. A graduate of the Allegheny General Hospital, she sailed with her comrades to England in March 1918 and then traveled on to France. Her unit as operated as part of Camp Hospital No. 21 at Bourbonne-les-Bains, but she later served at an evacuation hospital near Verdun. She died of pneumonia while serving there on September 27, 1918, possibly due to a complication from influenza. She initially received a burial in France near that hospital before her final burial at Arlington National Cemetery. The Katherine Mae Joyce American Legion Post, named in her honor, memorialized her in the years after the war.

• Kathryn Mae Joyce (Section 21, Grave 47) served as a nurse with the Allegheny General Hospital Red Cross Unit from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, designated as Hospital Unit “L” under the supervision of the War Department. A graduate of the Allegheny General Hospital, she sailed with her comrades to England in March 1918 and then traveled on to France. Her unit as operated as part of Camp Hospital No. 21 at Bourbonne-les-Bains, but she later served at an evacuation hospital near Verdun. She died of pneumonia while serving there on September 27, 1918, possibly due to a complication from influenza. She initially received a burial in France near that hospital before her final burial at Arlington National Cemetery. The Katherine Mae Joyce American Legion Post, named in her honor, memorialized her in the years after the war.

• Elizabeth H. Weimann (Section 21, Grave 4) of Haddon Heights, New Jersey, a graduate of the Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia, served as a nurse with Base Hospital 48. An immigrant born in Germany, she died on November 6, 1918 from pneumonia, likely brought on by influenza. Originally buried in France, she received a permanent burial at Arlington National Cemetery in 1921 In the 1923 book "American Homeopathy in the World War," Elizabeth and her comrades who died of influenza—including at least one other nurse—were remembered as “valuable members of the Unit” who “had performed splendid and earnest work and their loss … demonstrat[ing] beyond question that it is not necessary to do battle service in order to offer the supreme sacrifice.”

• Cornelia Elizabeth Thornton (Section 21, Grave 2), a native of Gloucester County, Virginia, served in the Army Nurse Corps as part of Base Hospital 58. She sailed to England on the SS Olympic on September 14, 1918. During that voyage, some sources indicate that she contracted influenza which turned into pneumonia. She died on September 28 or 29, 1918, in England, where she received an initial burial before being reburied at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1921, her hometown honored her by hanging her portrait in the Gloucester County Courthouse.

Perhaps the most famous nurse buried at Arlington Cemetery who may have died from the effects of influenza is Jane Delano. After the Armistice, Delano went to France to survey the conditions of the nurses still stationed overseas when she became ill. On April 15, 1919, she died, possibly as a result of complications from influenza, although it remains hard to be certain of the exact cause of her illness. No matter the cause, her death in France deeply upset American nurses who lost the leader who got them through the war and the pandemic. Delano’s final grave at Arlington National Cemetery rests among her sister nurses in the Nurses Section (Section 21), many of whom she led before and during World War I.

Standing guard over these graves is a permanent tribute to the bravery of American nurses during World War I: the Nurses Memorial. Army and Navy nurses raised the funds for this statuary memorial and dedicated it in 1938 to honor their fallen comrades. Designed by female sculptor Frances Rich in the Art Deco style, and sculpted out of Tennessee marble, the statue depicts the figure of a nurse in her uniform, cape flowing, as she keeps watch over the graves of the nurses surrounding her. In 1971, the memorial was rededicated to commemorate the service of Army, Navy and Air Force Nurses in all time periods.

Today, this memorial continues to honors the American nurses lost during the influenza pandemic. It serves as a reminder of the toll of that disaster on the United States and on our military. One hundred and two years later, as we commemorate the birthday of the U.S. Army and live through the tragedy of a pandemic in our own time, pausing to remember the American nurses who succumbed to influenza reminds us that we are not so different from the Americans of the past. Though they have traded their capes for scrubs, military and civilian nurses continue to play a major role in public health crises such as the coronavirus. Like their predecessors, they risk their lives each day to keep us safe. This blog post represents just the beginning of our research into the lives of the brave women who died during this pandemic and rest at Arlington. We are proud to be the stewards of their memory, and we have much more to learn about their service as we honor them.

Selected Sources

Barry, John M. “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America.” Smithsonian Magazine, Nov. 2017.

Budreau, Lisa M. “War Service by African American Women at Home and Abroad.” In We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity. Edited by Kinshasha Holman Conwill. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2019.

Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Dumenil, Lynn. The Second Line of Defense: American Women and World War I. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Fargey, Kathleen M. “The Deadliest Enemy: The U.S. Army and Influenza, 1918-1919,” Army History 111 (Spring 2019): 24-38.

Feller, Carolyn M. and Constance J. Moore, eds. Highlights in the History of the Army Nurse Corps. Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1995.

Gavin, Lettie. American Women in World War I: They Also Served. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1997.

Godson, Susan H. Serving Proudly: A History of Women in the U.S. Navy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Jensen, Kimbery. Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Jones, Marian Moser and Matilda Saines. “The Eighteen of 1918-1919: Black Nurses and the Great Flu Pandemic in the United States.” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 6 (June 2019): 877-884.

Schneider, Dorothy and Carl J. Into the Breach: American Women Overseas in World War I. New York, NY: Viking, 1991.

Zeiger, Susan. In Uncle Sam’s Service: Women Workers with the American Expeditionary Force, 1917-1919. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Related Content

• Nurses in the Spanish-American War

• Notable Graves: Medicine

• Notable Graves: Women

• Nurses Memorial

• Spanish-American War Nurses Memorial