Section 13 looking west. The rows of white-washed head boards gave this section the name of “Field of the Dead.” (Library of Congress)

Section 13 looking west. The rows of white-washed head boards gave this section the name of “Field of the Dead.” (Library of Congress)

At the end of April 1868, uniform rows of white-washed wooden headboards, each representing a gravesite of a fallen Civil War service member, filled the hills of Arlington National Cemetery (ANC). The property’s prominent ridgeline, marked by the Arlington House, offered stunning views of Washington, D.C. Little else distinguished this national cemetery as remarkable. While it contained the graves of some 16,000 individuals and spanned 200 acres, Arlington was only one of approximately 74 national cemeteries established beginning in 1862, during the Civil War.

Between ANC’s creation on May 13, 1864 through December 1865, the U.S. Army interred more than 12,000 service members at ANC. After the war, the Army reinterred thousands more at Arlington in 1866 and 1867. Following its long-standing ideology of leaving no one behind, the Army had begun an aggressive campaign in early 1866 to locate its fallen service members buried in temporary cemeteries across the United States. As a result of this Federal Reburial Program, by 1868, the remains of about 4,000 service members originally buried in the D.C., Maryland and Virginia area were reburied at ANC. Of those, 2,111 unidentified men were entombed in the Tomb of the Civil War Unknowns, located behind the Arlington House.

The U.S. government bore the full expense of burials for the fallen in its national cemeteries beginning in 1862. However these federally administered cemeteries offered no prestige for those buried in them. National cemeteries were seen as “potters’ fields” or “pauper’s fields”—burial grounds for those whose families did not have enough financial resources for a burial at a private cemetery. During the horrific carnage of the Civil War, the cost of private burials proved prohibitive to many families across the United States. The expenses included paying to have a fallen service member embalmed, the purchase of a shipping casket and the transportation of the remains home. Thus, burials at national cemeteries showed only that the deceased’s family did not have the financial means to bring their lost loved one home.

Arlington’s history as a quiet and scenic cemetery ended abruptly on May 15, 1868, when Major General (retired) John Logan (pictured, right), in his role as the Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), declared May 30 the first national Decoration Day. All U.S. veterans, from the Army, Navy, Marines and Revenue Cutter Service (today’s Coast Guard), were eligible to become members of this veteran service organization. The GAR became a large, influential and powerful political organization. Logan’s declaration therefore carried significant weight. His order effectively made Decoration Day an annual national day of remembrance to honor fallen Civil War service members. This commemoration took the form of visiting gravesites and decorating them with flowers—hence the designation of Decoration Day. Within a decade, Americans used the terms "Decoration Day" and "Memorial Day" interchangeably. It was not until 1971, however, that the day received its official designation as Memorial Day and the date changed to the fourth Monday of May.

Arlington’s history as a quiet and scenic cemetery ended abruptly on May 15, 1868, when Major General (retired) John Logan (pictured, right), in his role as the Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), declared May 30 the first national Decoration Day. All U.S. veterans, from the Army, Navy, Marines and Revenue Cutter Service (today’s Coast Guard), were eligible to become members of this veteran service organization. The GAR became a large, influential and powerful political organization. Logan’s declaration therefore carried significant weight. His order effectively made Decoration Day an annual national day of remembrance to honor fallen Civil War service members. This commemoration took the form of visiting gravesites and decorating them with flowers—hence the designation of Decoration Day. Within a decade, Americans used the terms "Decoration Day" and "Memorial Day" interchangeably. It was not until 1971, however, that the day received its official designation as Memorial Day and the date changed to the fourth Monday of May.

The first Decoration Day on May 30, 1868 did not live up to its billing as a “national” event, since former Confederate states would not take part in the memorialization until after World War I. Nonetheless, it had a profound impact on Arlington National Cemetery’s history. As part of Logan’s proclamation, the event set a precedent that has continued for more than 150 years. Each year, the official start of America’s day of remembrance begins when the president, or other senior government official, arrives at ANC to address the nation and, since 1921, to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Since that first Decoration Day at ANC, the cemetery has morphed from being just one of the many Civil War national cemeteries, to a unique place of honor where veterans wanted to be buried.

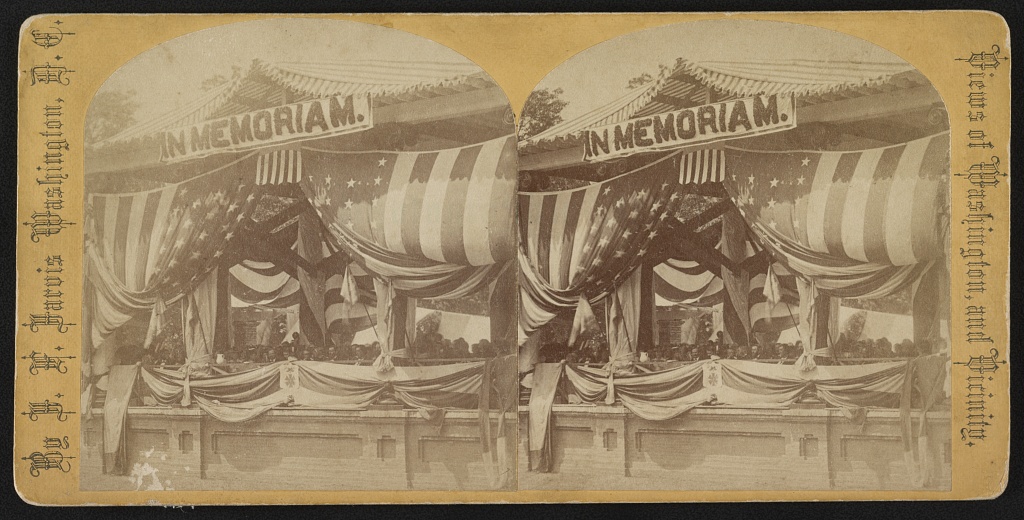

First Decoration Day held at the Tanner Amphitheater in 1873. Seated in the center is President Ulysses S. Grant and John Logan. (Library of Congress)

By the early 1870s, the rising importance of Decoration Day changed ANC’s status. When the Army constructed the first memorial amphitheater at the cemetery in 1873 (now called the Tanner Amphitheater), an average of 25,000 individuals participated in Decoration Day commemorations. Civil War veterans, who in a time of peace could be buried anywhere, clamored for a gravesite plot at Arlington. They wanted to be associated with the honor that now came with the cemetery’s annual memorialization. They also wanted to rest eternally near their former comrades.

The demand for burial space led to the creation of several additional burial sections at ANC, as well as plans for the cemetery’s first expansion, completed in 1897. Requests for burial from former Civil War officers led to the establishment of three new “officer” sections—the Western, Eastern and Southern Sections (today Sections 1, 2 and 3, respectively). National cemetery policy dictated that burials be segregated by both rank and race. Arlington’s segregation began on June 15, 1864, when Arlington transformed from a military cemetery to a national cemetery by order of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. These practices remained in place until President Harry S. Truman’s 1948 executive order which desegregated the military and national cemeteries.

Memorial Day observance in the Memorial Amphitheater, held in the 1920s. (Library of Congress)

Additional Decoration Day events, year after year, increased the public’s awareness of Arlington. As ever-growing numbers of Civil War veterans opted for burial at the cemetery, public perceptions of Arlington changed. Individuals started to refer to Arlington as the “nation’s premier military cemetery” and “America’s most sacred shrine.” None of this would have occurred without the cemetery’s connection to Decoration Day. In less than a decade, ANC transformed from an ad hoc military cemetery to one of extreme national significance. This development cemented Arlington’s position of prominence in the minds of many Americans. Arlington National Cemetery continues this legacy through today, even during the global response to COVID-19.

See also: