by Tim Frank, ANC Historian

October 13, 1915 was probably like any other day for Robert Thurston Frank. He would have left his row house on Columbia Road NW in Washington, D.C. and headed to his office in the District of Columbia’s Electrical Department, where he worked as a clerk. Later that day, just across the river in Virginia, Civil War and Spanish-American War veterans and dignitaries gathered to watch President Woodrow Wilson lay the cornerstone of Arlington National Cemetery’s Memorial Amphitheater. Photographs of the ceremony show the cornerstone being lowered over a small memorabilia box (commonly known as a time capsule today) that contained important documents and mementos of the day. It was a proud day for the nation and the veterans present, as the grand marble structure started to rise from the cornerstone to memorialize service and sacrifice from the American Revolution through the Spanish-American War. The amphitheater, which later opened to the public on May 15, 1920, would provide a larger, grander venue for the annual Decoration Day (now called Memorial Day) ceremony at the cemetery, held every May since 1868.

Robert Frank (pictured, below right) probably read about Memorial Amphitheater’s dedication ceremony in the next morning’s Washington Post or Washington Times. Little could he imagine that over 100 years later, I, his great-grandson and a historian at Arlington National Cemetery, would be the first to lay hands on the contents of the memorabilia box that had been carefully sealed on October 12, 1915.

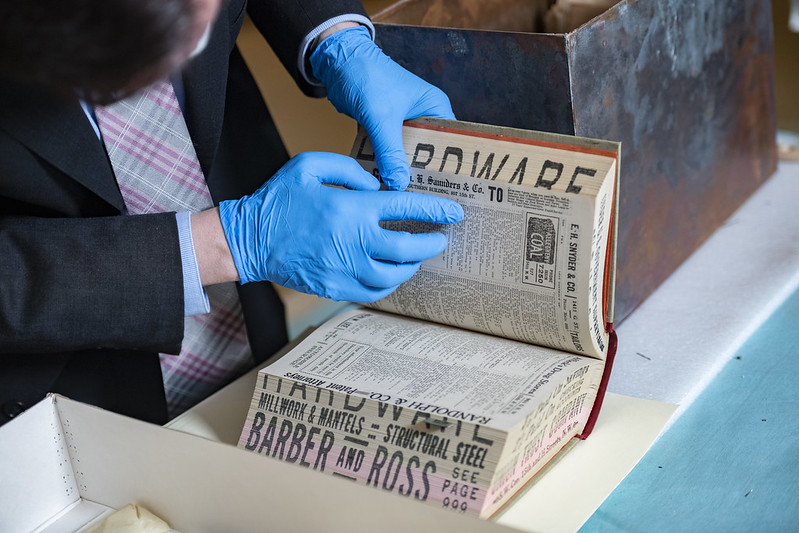

Untouched for over a century, the memorabilia box was recently removed by experts at Arlington National Cemetery, as part of the centennial commemoration of Memorial Amphitheater’s dedication. The group included myself, a conservator and facilities maintenance staff. We gathered in the basement of the Amphitheater to carefully open the copper box, whose contents included:

-

maps and plans of Washington D.C.

-

six coins (one of each cent, contributed by Colonel William W. Harts, who retired as a brigadier general and is laid to rest in Section 3, Grave 3907)

-

uncirculated stamps with images of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin

-

an American flag (with 46 stars, although there were 48 states in 1915)

-

copies of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution

-

a Bible (signed by Thomas Hastings, architect of the amphitheater)

-

a signed photograph of President Woodrow Wilson

-

local newspapers (Washington Post, Washington Times, Washington Herald and The Evening Star)

-

an advance copy of the dedication ceremony program

-

a Congressional directory

-

Civil War veterans’ pamphlets

-

the Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia, an annual directory of city residents

These items were carefully tied, wrapped and arranged in the inner box, which was soldered shut. That box was then surrounded by pieces of plate glass to keep an air gap between it and the larger copper box, ensuring that no condensation would damage the precious documents and mementos inside.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience to be the first person to remove the items that hadn’t seen the light of day since 1915. When I found the Boyd’s Directory, I looked up both sides of my paternal family, the Franks and the Lansdales, and I found an entry for my great-grandfather, "Frank, Robt, clk dist r 607 Columbia rd. nw." I then turned to the Lansdales, but did not find my grandmother’s parents (they appear in later directories).

It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience to be the first person to remove the items that hadn’t seen the light of day since 1915. When I found the Boyd’s Directory, I looked up both sides of my paternal family, the Franks and the Lansdales, and I found an entry for my great-grandfather, "Frank, Robt, clk dist r 607 Columbia rd. nw." I then turned to the Lansdales, but did not find my grandmother’s parents (they appear in later directories).

I suspected when I opened the box that I would find Robert Frank’s name in the Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia. The Frank and the Lansdale families are long-time District residents, an unusual fact in this transient city. Robert Thurston Frank had three children, including Elmer Dundy, born in 1918, who would become my grandfather. He married Virginia Lansdale of northwest D.C. and raised three sons, including my father, Larry Frank.

Raised on weekend trips to museums and battlefields, and hearing stories of my family’s experiences of Washington D.C. over the last 100 years, it was no surprise that I came to love history and eventually became a historian at this cemetery. Opening the memorabilia box has been one of the highlights of my career. Historians get the rare and treasured chance to hold pieces of our country’s history in their hands, and it was a privilege to find our family roots as well. Whether our ancestors participated in events like Memorial Amphitheater’s dedication ceremony or, like my great-grandfather, were simply fulfilling a clerk’s day of work, they were witnesses to great moments in history.